Voici quelques extraits tirés de traductions de documents sur les Beaux Arts

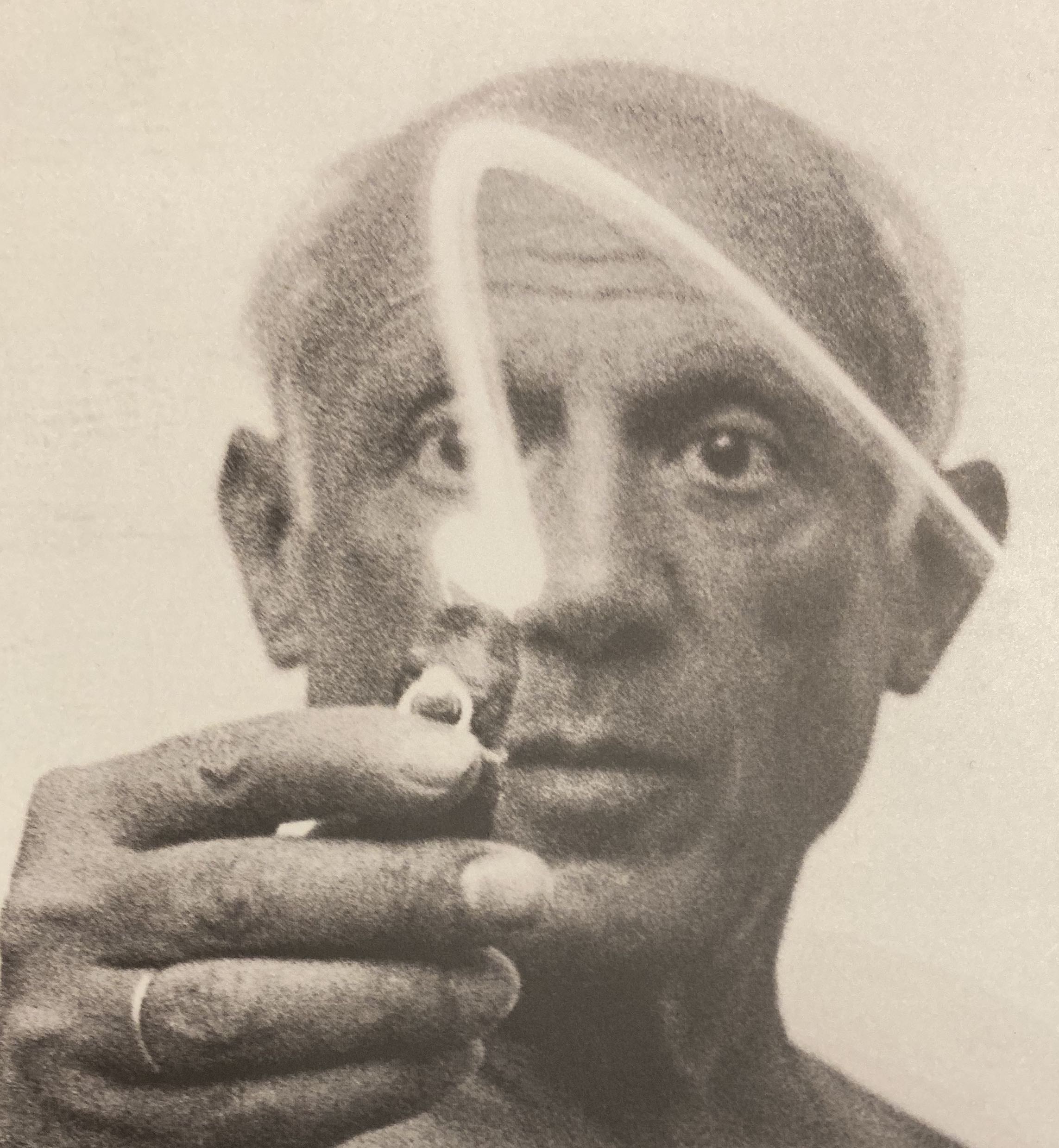

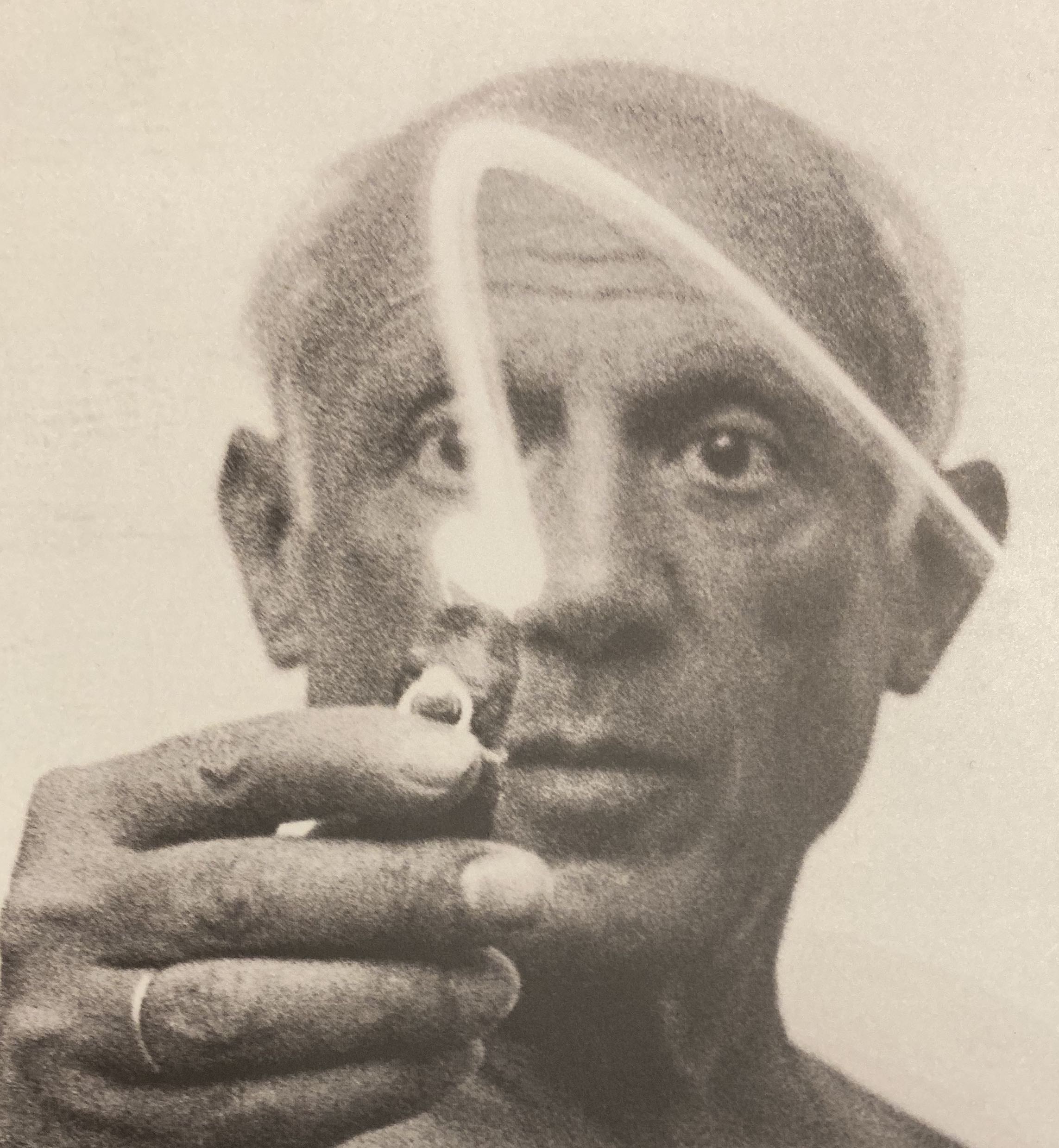

Picasso

Pour moi, Pablo Picasso est né le 8 avril 1973. Oui, mon grand-père est né le jour de sa mort.

Auparavant, il n’existait pas, ni dans mes rêves ni dans la réalité. Il n’existait que sur les murs, à la fois très présent et très abstrait. Quelqu’un dont on me parlait, parfois, mais que je ne voyais jamais.

Au lycée, tous mes copains avaient un grand-père, qu’ils rencontraient souvent le dimanche. Moi non. Le plus curieux, c’est que ça ne me manquait guère. Ils avaient des photos de famille. Moi, j’avais des portraits de famille : ma mère enfant, ma grand-mère rêveuse – et des objets peints que l’on appelait natures mortes, même si je ne comprenais pas bien comment une cafetière ou un morceau de pain pouvaient vivre ou mourir…

Le 8 avril 1973, tout a changé. Toute cette nature « morte » s’est réveillée ! |

I never knew Pablo Picasso; my grandfather only began to come to life for me the day he died, on 8th April 1973.

Before that, he had no existence, either in my dreams or in reality. He only existed on walls, omnipresent but at the same time quite abstract. Someone that people talked about to me occasionally, but whom I never saw.

All my school friends had grandfathers that they often went to see on Sundays. I didn’t. The oddest part was that I didn’t really miss that. They had family photos. I had family portraits: my mother as a child, my grandmother looking pensive – and painted objects for which the term ‘still life’ was used, though I didn’t understand how a coffee pot or a piece of bread could be alive or dead.

But on 8th April 1973, all that changed. All this ‘still life’ was reanimated! |

Olivier Widmaier Picasso, Picasso, portrait intime, ©Albin Michel, Paris 2013

Peinture

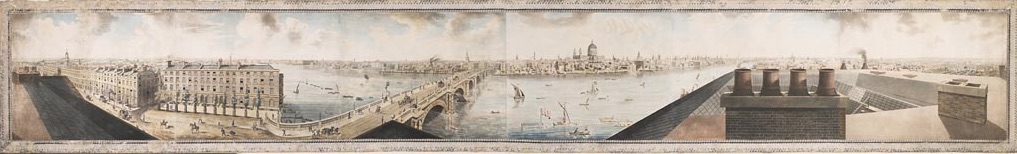

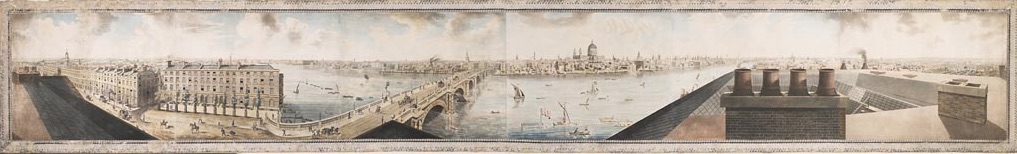

Article sur les panoramas, traduit de l’allemand pour le journal Connaissance des arts

L’origine du panorama

„Doch faktisch war es der irische Miniaturmaler Robert Barker, ein mittelmäßiger und eher erfolgloser Künstler, der „dummdreist“ genug war, den Traditionsbruch zu wagen und ein Rundumbild nicht nur zu denken, sondern auch prakisch zu versuchen. Da ihm aber alle seine Kollegen davon abrieten, denn ein solches Bild würde nicht „funktionieren“, setzte er, weil ihm die eigene Zeit dazu zu schade war, seinen 12jährigen Sohn Henry Asten Barker an die Aufgabe, eine Rundumsicht auf Edinburgh vom Carlton Hill aus in einer Reihe von an einander anschließenden Veduten aufzunehmen. Die an den Stoßlinien der einzelnen Blätter sich ergebenden „Brüche“ wurden dann perspektivisch korrigiert und so die Serie zu einem Rundum-Bildstreifen harmonisiert. Anschließend wurde die Zeichnung farbig ins Große transponiert. Wider alles Erwarten „funktionierte“ dieses Bild und vor allem fand großen Anklang beim zahlenden Publikum.

1787 meldete Barker sein „Gemählde ohne Gleiches“ (d.h. neu ohne Vorbild) zum Patent an. Dass die Zeitgenossen diese Erfindung als bisher nicht dagewesene technische Innovation akzeptierten, unterstreicht die Besonderheit dieser neuen Kunstform.“ |

“In fact, however, it was an Irish painter of miniatures, Robert Barker, a mediocre and rather unsuccessful artist, who was so ‘presumptuous’ as to break with tradition and attempt, not only to think about an all-round picture, but actually to put the idea into practice. However, as all his colleagues advised him against it, on the grounds that such a picture would not ‘work’, and as he himself could not afford to waste time on it, he gave his 12-year-old son, Henry Asten Barker, the task of working up an all-round view of Edinburgh seen from Carlton Hill by combining a series of interconnecting vedute. The perspective of the ‘discontinuities’ arising where the sheets met was corrected, harmonizing the series of pictures to form a continuous all-round strip. Lastly, the drawing was transposed into full size with colour. Confounding all expectations, this picture ‘worked’ and, most important, proved extremely popular among the paying public.

In 1787 Barker applied for a patent on his ‘painting without precedent’. The fact that his contemporaries accepted this invention as a previously non-existent technical innovation is evidence of the distinctiveness of this new art-form.” |

Connaissance des arts, Special Issue no. 721/1

Photographie

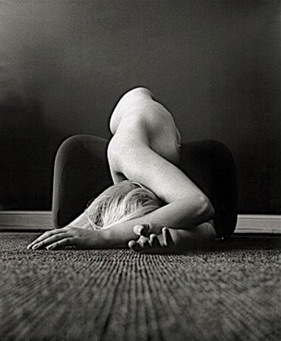

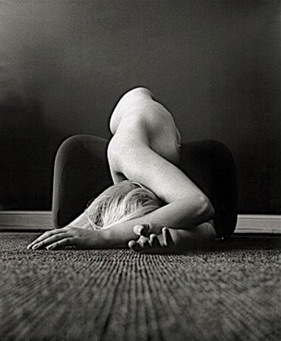

Über die Aktfotografie von Karin Székessy heißt es, sie habe ihr den weiblichen Blick beigebracht.

Um so spannender erscheint der Versuch einer Neubetrachtung – vor allem vor dem Hintergrund eines immer noch stark geprägten männlichen Blickes auf den weiblichen Körper und die gegenwärtige Rezeption und Wahrnehmung dieser Betrachtungen. Székessys Frauenakte wirken weniger entblößt und voyeuristisch aufgeladen. Im Vordergrund ihrer Akte steht ein ihr selbst vertrauter weiblicher Blick. Die Frauen wirken frei, bescheiden und fast unauffällig – sie werden dadurch unantastbarer, was jedoch nicht bedeutet nicht, dass Eros abwesend ist, wie es seinerzeit im Text ihrer Ausstellung in der Berliner Galerie Werner Kunze steht.Extrait du catalogue d’une exposition de photographies pour la galerie Chaussee 36, à Berlin |

It has been said of Karin Székessy’s nude photographs that she brings a woman’s eye to the subject.

This makes such an attempt at a fresh view all the more compelling – especially against the backdrop of a perception of the female body still essentially masculine, and the current reception and awareness of these attitudes. Székessy’s naked women seem less denuded and less voyeuristically charged. In the foreground of her nudes is a more self-confident woman’s perception. These women seem free, modest and almost unremarkable – they thereby become more untouchable, though this does not mean that Eros is absent, as was asserted at the time in the text accompanying her exhibition in Berlin’s Werner Kunze gallery. |

![]()

![]()